Interview with Anna De Mutiis and Pilo Moreno

Trigger warning: This interview discusses immigration detention, mental health distress, psychological abuse, and systemic violence.

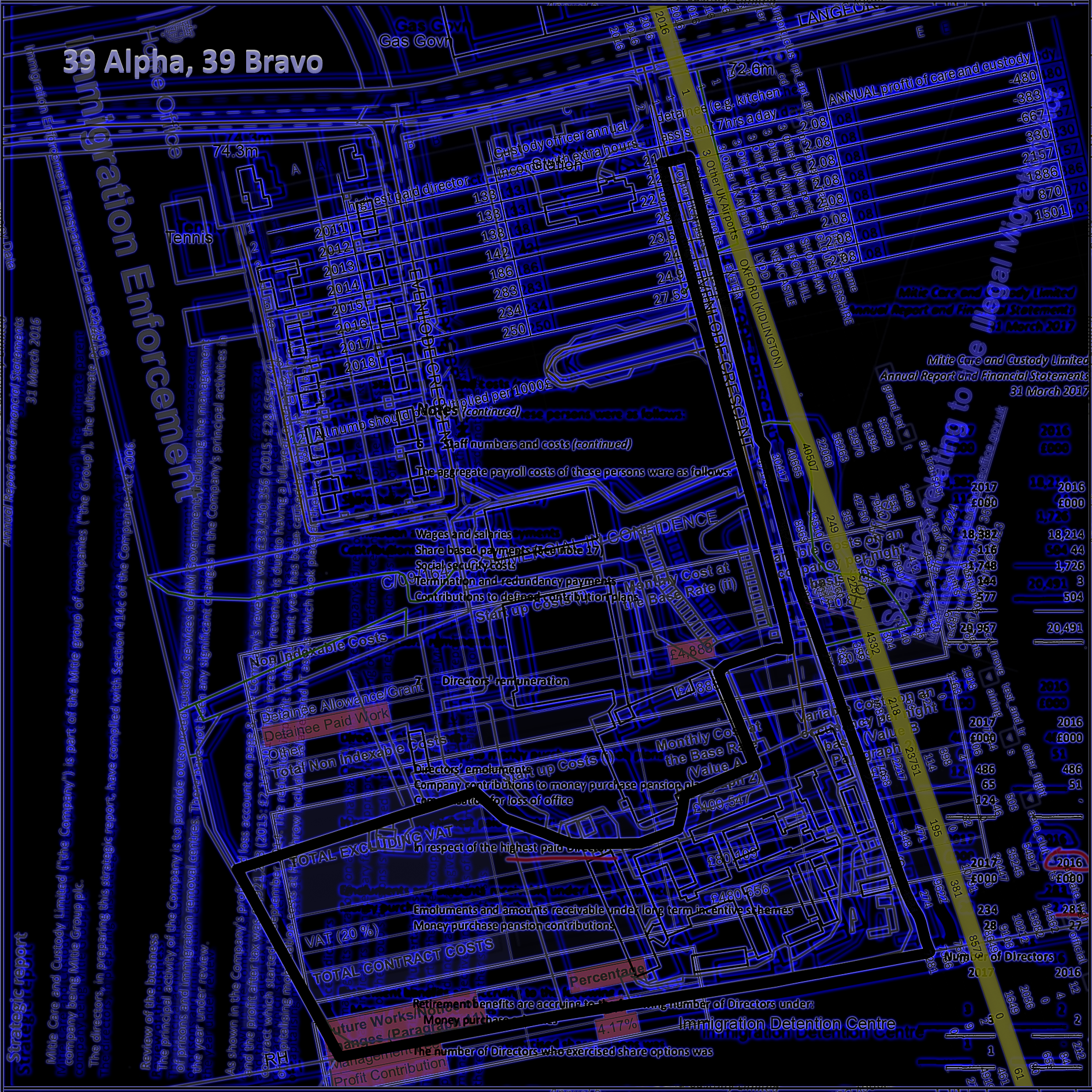

39 Alpha, 39 Bravo – The Sound of Detention’s Economies is an audio work by Earrational Measures, co-created by artist-researcher Anna De Mutiis and musician and expert-by-experience Pilo Moreno. The piece uses data sonification to trace the economies of profit and exploitation inside Campsfield House Immigration Removal Centre across a single 24-hour cycle in 2016, the year Moreno was detained there for over five months.

Built from financial data, first-person narration, and sound design, the work renders audible the daily income of three actors within the detention system: a company director, a custody officer, and a detained worker. By compressing one day into a four-minute loop, the track exposes extreme income disparities while reflecting the monotony, disorientation, and loss of agency that define life in indefinite immigration detention. Sound choices are led by lived experience, transforming statistics into rhythm, texture, and repetition.

The project emerges from a long-term collaboration between De Mutiis and Moreno, rooted in music workshops, research, and prior audio work addressing detention, mental health, and migration. It also responds to the opacity surrounding the financial structures of privately run immigration removal centres, where commercial confidentiality often shields profit from scrutiny. 39 Alpha, 39 Bravo proposes sound as a political and analytical tool: one that centres experts by experience and invites listeners to engage emotionally and critically with data that is usually abstracted or obscured.

Following a £70 million refurbishment, Campsfield House reopened on 3 December 2025 under a new six-year contract awarded to MITIE Care & Custody, the same company that managed the centre prior to its closure. The interview below accompanies the release of 39 Alpha, 39 Bravo and appears exactly as provided by the artists, without edits or paraphrasing.

How did your respective backgrounds and lived experiences shape the conception of 39 Alpha, 39 Bravo?

Pilo and I met inside an Immigration Removal Centre (IRC), in Campsfield House in 2016. I was delivering a music workshop and he was in the workshop, steady hands moving on the frets of a bass guitar I just brought in the room a few minutes earlier.

Pilo has always been playing different instruments since childhood and he moved across continents thanks to music and music projects; I have always been interested in how music shapes identities and understanding of the world and, after dedicating a few years of my studies to anthropology of music, I went back to playing live and I started working as a music workshop facilitator.

Anna De Mutiis

We can then say that music, migration and social justice issues have been constants in our friendship and artistic collaboration, as well as part of our life trajectories. Once released from Campsfield House, Pilo and I explored different ways of addressing the topic of detention through music and sound (resulting in a live music band, and the creation of a podcast about life in detention with its lasting mental health impacts on post-detention life).

Over the years, we kept returning to an overlooked topic: the financial gains that private corporations extract from people's detention.

This is why we embarked on this new project based on data-sonification.

Having spent five months detained, Pilo witnessed firsthand the economies governing these centres, but getting a clear picture with evidence proved difficult. He wanted to expose both the complexities of life inside and the inhumane treatment enabled by profit-driven companies with state complicity.

For Pilo, talking about his detention has always been difficult yet necessary—a way to make sense of such a traumatic experience. This new project offered him a way to engage people in this conversation while also transforming his experience into something meaningful and creative through an artform he masters: music.

My background in Migration and Diaspora Studies made me aware of how academic and journalistic language often fails to centre the perspectives of experts by experience when addressing social justice issues. My time leading music workshops in detention centres left me equally frustrated with mainstream media's decades-old habit of framing migrants as either criminals or objects of pity. We experimented with sound as a way to transform sterile statistics and technical jargon into something engaging and accessible. This approach allows people with lived experience to become the data analysts and commentators themselves—a powerful shift from mainstream media's reliance on external experts.

The piece follows a single day inside Campsfield House IRC. Why was it important to focus on a 24-hour cycle, and what does that repetition say about daily life in detention?

Photo credit: “Campsfield house seen through the fence” by Pierre Marshall, CC BY 2.0.

Once we selected our data—comparing the income of three different actors within the centre—and settled on a four-minute track for focused listening, we faced a challenge. The director's income was so much higher than the others that we needed to find the right timeframe (a day, a month, a year?) to make the disparity audible and comprehensible. One day condensed in four minutes was the best choice for us to be able to hear this disparity, with £1 earned by the director occurring every 0.3 seconds. Ultimately, in the first step of the composition, we let the data drive the music rather than imposing our own artistic preferences.

However, the choice of a 24-hour cycle served multiple purposes beyond the practical. It allowed us to capture the repetitiveness and lack of agency that defines life in detention—a monotony that takes an extreme toll on mental health and contributes to the wider process of dehumanisation that’s intrinsic in this place. The four-minute piece can be played in an infinite loop, with listeners able to enter at any point, mirroring how each day in detention bleeds into the next. This reflects the warped sense of time generated by dull repetition, which can lead to profound disorientation and hopelessness, making it nearly impossible to maintain a sense of self or envision a future beyond those walls.

The UK is the only country in Europe, and one of the few worldwide, that permits indefinite immigration detention. Waiting becomes a form of control designed to break down people's capacity and willingness to fight their cases. Detainees often feel powerless—stuck in limbo—not knowing when their lawyer will respond, whether they'll get a bail hearing, or if a deportation order will arrive first. Daily activities repeat at identical times, marking an endless loop where, as the track's ending lyrics state, “you don't know if it's the same day or a different day.”

You use the daily income of people working and detained at Campsfield House as a sonic element in the piece. How did you choose those figures, and how did they become sound?

Why these figures:

Given the extensive data we had collected in our research, we wanted to shed some light on the different layers of exploitation at stake in IRCs and the narratives and processes that enable this exploitation to happen, both at a macro and micro level. We noticed that, in the year Pilo was detained—2016—the income of the highest paid director of the company managing the IRC was extremely high. We thought that the best way to show how this profit is generated was to compare the income of three different roles within the detention centre's hierarchy, revealing how a process of accumulation by dispossession occurs on a systemic level.

Hearing the inequalities of income between the company’s director and a working detainee (roughly £700 vs £7 in one day) serves as a background for stories of profit generated through inadequate basic provisions (the 5 cm mattress, the iron bed, the unhealthy blue juice), as well as stories of detainees paid better rates while exploited by illegal syndicates operating outside detention.

Moreover, we wanted to also include custody officers in this exploitative system. Custody officers employed by private corporations are often paid very low wages and operate with insufficient training to deal with the diverse population and the acute mental health distress episodes that can occur inside IRCs. They are thus caught in between this system of exploitation, on one hand serving it, while on the other being underpaid and thus exploited by the same system they are serving.

We hoped that these stark numerical contrasts would speak for themselves through the sound chosen.

How they became specific sounds:

Given his personal experience and relation with the context of detention, Pilo took on the task of choosing which sounds he would consider more appropriate to associate with certain data. The sound associated with the custody officer making £1 is a sound that evokes the sound of videogame’s character Mario Bros when collecting a coin. This is a reference to the custody officer being part of a system for which you must work hard to get just one coin (a low wage), while at the same time having to comply with the rules of the game.

The sound associated with a detainee earning £1 (corresponding to 1 hour of work) is the sound of chains moving on the floor. Pilo chose this sound because this sound can be very similar to the sound of a bunch of coins falling on the ground. He argues that, in his experience, as you don’t know your release or deportation date, you might try to get a job to make some money inside the centre, but in this way the work chains you to that place, to that whole system. This choice of sound is for him a way to ask the question: when you earn £1 inside an IRC after one hour of menial duties work, is it money or is it chains?

Finally, given that the sound of the earning of the company director occurs too often to keep track of it (becoming the hammering kick drum sound persistent throughout the whole track), we decided to add a reminder every time the director would make £100. Pilo chose the sound of a whip with a long reverb tail. Hinting at the idea of a recurring and ever-evolving form of modern-day slavery, this clearly addresses issues of racial capitalism and accumulation by dispossession that informs the border control industry.

Pilo Moreno

What do you hope listeners take away from hearing exploitation rendered this way, rather than explained through words or statistics?

Statistics can be pretty dry, and words often come loaded with complicated baggage. Using sound and music to address this issue engages the more emotional, visceral side of the listener.

Music and sound design allowed us to convey emotions from our conversations about life inside detention that would be impossible to express in words. We used specific effects such as noises, delays, and echoes to evoke these haunting emotions.

Borrowing from sociologist Avery Gordon’s concept of haunting as “the screaming presence of that which appears not to be present”, these effects aim to sonically include all those presences that cannot be grasped, fully understood, or explained, yet linger and influence our past, present, and futures—both individually and collectively.

The tail of a scattered echo of a pigeon’s flapping wings on a roof, inhabiting unfamiliar frequencies, can sonically testify to all those ‘leftovers’ never accounted for in reports, statistics, or narrative stories. In a way, our experiment was to allow the audience to listen to these ghosts and include them in the conversation.

In a recent listening session, someone mentioned they had read many reports on exploitation inside detention, but it was only when hearing the stark income disparity juxtaposed with stories of detainees paid better by illegal syndicates outside detention than by the system inside, that it truly hit them. The music spoke to their gut in a way the reports never had—bypassing rational analysis to land somewhere deeper.

After a £70 million refurbishment, Campsfield House has been reopened on the 3rd of December 2025 by the current government, who awarded a six-year contract to the same company that was managing the centre when it closed, MITIE Care & Custody.

For more info and to support its closure visit the Coalition to close Campsfield website HERE.

To support people detained in IRCs please consider endorsing the work of Bail for Immigration

The 10 minutes track, released under the collective name ‘Earrational Measures’ and available to listen HERE, is accompanied by a short introduction explaining the data-sonification process, as well as the rationale behind the sound design.

For further discussion or to enquire about possible collaborations, please get in touch at earrationalmeasures@protonmail.com.

Credits

- Pilo Moreno: voice, bass, data sound assignment, additional synths

- Arturo Moreno: synths

- Anna De Mutiis: data-sonification, production, arrangements, sound design, initial narration

- Mixed by Anna De Mutiis

- Mastered by Ahmed Rezaie

- Cover art: Anna De Mutiis

- Visual Identity: Benedeserap

Pilo Moreno on Instagram & Earrational Measures